When in 2009, invited by the then-new director Labina Mitevska, the cult Spanish actress Victoria Abril reinvigorated the Brothers Manaki Festival in Bitola with her lucid presence, it was to be expected that Almodovar’s former muse would become part of a project by Sisters and Brother Mitevski Production. Her acceptance of the lead role in Teona Mitevska’s new film subtly influenced the author herself, so that we see opening credits that in their sensibility very much resemble the Spanish master’s projects, and even the elements forming part of the story itself—(anti)heroines, homicide, suicide, incest, revenge—are all part of the folklore of Pedro, who has made some of the most exciting pieces of European cinema in the last two decades.

It is precisely the cinema of the old continent—if we attempt to generalise and place it all in the same folder, even though it has a whole wealth of diversity—that provoked Teona Mitevska, who obviously decided to approach the desired European standards with her third feature-length creation and make a film that resembles all that we have seen in the abovementioned Spanish, but also in the French, German, Belgian, or Austrian schools of cinema. After searching for the primal authorial scream within in her confusing debut How I Killed a Saint (Како убив светец, 2004) and the superficial touching upon certain sensitive subjects in I Am from Titov Veles (Јас сум од Титов Велес, 2007), in her third attempt Mitevska finally realises her intention successfully, making a ‘pure’ film in which a number of well-crafted solutions are executed quite well and do form part of that European tradition.

The Woman Who Brushed off Her Tears starts on a fierce note. The wise decision for the first, French scene, in which the son kisses his mother and then, after telling her that he might have been molested by his father, jumps off the balcony and kills himself, hooks the viewer immediately and allows for the development of a terribly emotional tale that might lead anywhere. Mitevska, however, decided on a minimalist approach in which she carefully measures her characters’ emotions, leaving the viewer in a clandestine suspense, wondering what comes next. The long takes in which we only see the face of one protagonist and only hear the voice of the other often capture more than if the scene were edited in a classical manner. For this the author had the wholehearted help of—or better yet, all the credit goes to—the Hungarian cinematographer Mátyás Erdély, who, in order to better capture the characters’ emotions, seems to have chosen the best possible camera angles, whereas his photography is a whole different story since with its grim voluptuousness is like an additional, separate character in the film.

As a counterpoint to the French plot, we see the Macedonian, that is, the Yuruk story of the curious Ajsun, who with her son Ilkin waits for the return of the boy’s illegitimate father from abroad so that they could finally become a family, despite the objections from her own father, who does not even want to hear of such a development. The traditional Turkish community from the village of Kodžalija near Radoviš was immortalised by Robert Jankulovski with his photo lens a few years ago, and then by Biljana Garvanlieva in her documentary Tobacco Girl (Девојчето што береше тутун), recipient of several international festival awards. This time Labina and Kaeolik Mitevski play fictional film versions of the authentic Yuruks, where both of them, unfortunately, failed to escape the modern features of their own personalities. Simply put, the transformation of a character from a traditionalist into a proper rebel does not occur only by aggressively chewing gum or by a simple motorcycle ride. Nevertheless, this part of the story does work to a point since it has a lot in common with the French plot, in the end creating a vicious cycle in which both women, as representatives of different societies and cultures, struggle to preserve their respective undermined identities. Along these lines, there are two crucial scenes in the film that will not leave you indifferent, and in both Abril’s character is the protagonist. In the first scene, while her husband is snoring, after she previously objected to his loud chewing, she decides not to reproach him, and the strength she accumulates from inaction makes her levitate in the air, as a nice and effective portent of the denouement that is to come. The second scene is the crucial coming face-to-face with the wolf that simply reinvigorates you for a moment.

After these strong gems of scenes, in the final part, when the divine crescendo is to be expected, the events surrounding the hunt are surprising in their predictability and seem to dilute the impressions gathered in the previous ninety-odd minutes. Nevertheless, the conclusion remains that this film is Teona Mitevska’s most mature project to date and that it will have a successful lifespan at festivals and in movie theatres, considering its promising start on the international stage at the prestigious Berlinale, as well as Labina Mitevska’s great prowess as a producer.

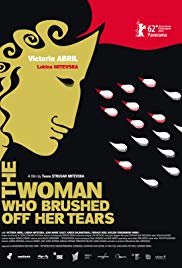

THE WOMAN WHO BRUSHED OFF HER TEARS (Drama, 2012)

(ЖЕНАТА ШТО СИ ГИ ИЗБРИША СОЛЗИТЕ)

(MK / SLO / BEL / GER, 103 min)

Director and writer: Teona Strugar Mitevska

Cast: Victoria Abril, Labina Mitevska, Jean-Marie Galey, Arben Barjaktaraj, Firdaus Nebi, Dimitar Gorgievski, Kaeliok Mitevski

(Published on 2nd May 2012 in the „Nova Makedonija“ daily)